Disclaimer: I have not yet read the books, but watching this first movie convinced me to read the rest. If something I write here is addressed in detail in the book, I'd love for readers to suggest page numbers, references.

And I loved the movie even while disturbed by its theme. I loved it enough to watch it again, and without going into boring detail as to all the things I appreciated about the movie, I'll name these--the casting of Woody Harrelson, Lenny Kravitz, Jennifer Lawrence, and many others, was simply perfect, many of the new actresses and actors were outstanding, and what isn't there to like about a dystopian movie like this if you are a sci-fi geek?

I. This is a movie about them watching them.

Or actually, it's a movie about us watching them watching them.

Or you could say it's a movie about us watching us watching them watching them watching them.

What?

Take the last point: It's a movie about us watching us (because we have been for quite some time now analyzing who is watching this movie, and how many, and how much money was spent on it in the first week, and how many people are reading the book, and so on--and now you can even buy make-up in order to not only watch them but also look like them).

It's a movie about us watching them (because we're watching the movie). It's a movie about them watching them (because all the fans in the capitol are watching the games). It's a movie about them watching them watching them (because the capitol and people in control are watching how the games affect the Districts and the people in them, and then modify the games to suit their needs).

And all of these "nestings" of perspective, this post-modern self-awareness about viewer and audience self-complicity in the gaze of the other, is pulled off effortlessly, never pedantic. In fact the flair with which it is accomplished results both in the power of the movie (and I assume book) to attract us, and the danger is perhaps that we may not notice the extent to which we are complicit in the elicitations. How many viewers will educe this point?

And all of these "nestings" of perspective, this post-modern self-awareness about viewer and audience self-complicity in the gaze of the other, is pulled off effortlessly, never pedantic. In fact the flair with which it is accomplished results both in the power of the movie (and I assume book) to attract us, and the danger is perhaps that we may not notice the extent to which we are complicit in the elicitations. How many viewers will educe this point?Another way to come at this is to ask: Can media via media engage in self-criticism? Can a blockbuster movie about a blockbuster reality-show-to-end-all-reality-shows successfully pull of the kind of self-critique of media it seems to be attempting to? I would argue tentatively that it can, to a degree, but it engenders all same dangers of such a medium that were illustrated in full when U2 went on the Popmart tour.

II. The Scapegoat Mechanism

If ever there was an apt portrayal of mimetic desire in cinema, this movie is it. I walked out of the theater wondering to myself, "How long will it take before we get a Girardian analysis of this movie?" If someone hasn't done it already, here's mine in miniature.

Mimetic desire is when you want something that someone else wants. The violence that ensues as a result of competing desires is sometimes called a scapegoat mechanism. The scapegoat is the victim onto which the violence of competing desires is thrust, and typically these scapegoats are either killed or cast out of community. In the case of The Hunger Games, it is both. Social order is restored or controlled when the scapegoat mechanism is enacted. In this narrative, there needs to be a price paid for the revolution, and so the games are established "forevermore" as the mechanism for "keeping peace."

However, as the Districts, and the people in the Capitol, all view the games simultaneously, there is a vicarious scapegoating that also happens. The wealthy capitol residents get to participate in that which they desire (to slum like the residents of the district) and the District residents get to see enacted what they desire (violent revenge, as well as hope that their youth might win). In both cases, the scapegoating mechanism offers only limited and temporary consolation, and as the president of the capitol knows all too well, the mechanism can fail quite easily if it offers too much hope, or only limited hope, or if it is modified in a way displeasing to the community as a whole.

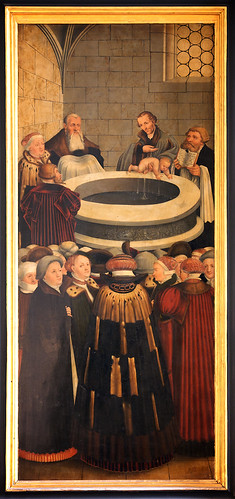

The question in a Girardian analysis of this mimetic desire--does the movie itself participates in the kind of "end of scapegoating" that is accomplished, for example (according to Girard) in the case of Jesus? For Girard, since Jesus is raised from the dead, the community is now made aware of the mechanism in such a way that it no longer needs to enact the mechanism anymore. The cycle has been broken.

Ostensibly, it would seem like this is Suzanne Collin's goal as well, to bring to awareness the violence enacted in such spectacle and so warn viewers away from it. Whether this is a successful strategy remains to be seen. For now, the movie itself IS spectacle, certainly re-enacting a scapegoating mechanism in all its gory and horrific detail--but will it change anything? That is another question.

For example, will it at all raise our awareness of all the other spectacles (certainly of a less overtly violent sort) to which we pay tribute? The most recent violent mechanism I imagine few would consider such was the last Mega-Millions lottery. Here millions of dollars that could have been used for all kinds of good were sacrificed at the altar of mimetic desire, the desire to have the desire of others, in this case incredible riches. However, this is a more subtle illustration of mimetic desire, not as blatant as a game set up for children to murder each other. Nevertheless, I believe the same mechanisms are in play.

If this point has intrigued you, I suggest two resources. First, you can read weekly meditations on the lectionary texts from a Girardian perspective at http://girardianlectionary.net/. Second, the greatest and most accessible writer bringing to life the Girardian perspective in theology is James Alison, whose web site offers a cornucopia of essays and other resources.

III. Hope Measured Out in Coffee Spoons

For my money, one of the most theologically poignant moments in the movie was when President Snow says to Seneca Crane, "Hope; it is the only thing stronger than fear. A little hope is effective, a lot of hope is dangerous. Spark is fine, as long as it's contained. So, contain it."

This is one of those moments in a movie where every theological bell in my entire heart and brain started ringing at once. Although this particular point deserves greater analysis, for now (at least in part because I'm reserving more insight on this for my sermon on Easter Sunday), the difference between hope measured out by despots, and the hope of the gospel, is how profligate the gospel is with hope. God in Christ just gives hope away, without measure. The movie, by pointing out that some use small measures of hope as a tease in order to control, offers profound truth at this point.

IV. Is Violence Redemptive?

Notice in the movie that the main characters, the ones we are hoping will win and carry us forward in the narrative, avoid, for the most part, engaging in any forms of "non-redemptive violence." So, for example, when Katniss witnesses Peeta teamed up with the violent and surviving faction in the games, she (and so also us as viewers) is horrified. She wonders, as do we--Has he engaged in killing that isn't redemptive?

Conversely, Katniss never kills anyone in the games, except for once, while defending herself and Rue. She indirectly kills one tribute by dropping a tracker jacker nest, and she kills Cato at the end, but only to save him from the dogs.

But we see the point--some kinds of violence are better than others. Inadvertent killing is better than direct execution style killing, killing in self-defense is better than killing to win (even though, in the way this game is set up, all killing is ipso facto self-defense). Even those in the capitol live at different levels in this tension. So Lenny Kravitz's character, though complicit in preparing young children for violent games, is as caring and helpful as he can be in the meantime. And so we identify with him more than others.

In fact, throughout the movie, the amount of sympathy we are asked to have with various characters is directly correllated to the level of their violence and whether it is redemptive or redeemable--or not.

At the conclusion, when Cato asks to be killed, he says, "I am dead anyway. All I know is how to kill." Hopelessness is defined as an inability to do violence towards good ends.

However, we ought to ask ourselves whether violence is ever, in the end, redemptive, and whether the scalability of violence in this movie (and just so pretty much every other movie like it) is actually faithful to the true place of violence in culture and society.

V. Is there a problem with spectacle?

On this last point, I do not fault the movie in any way. Movies are made to sell, they need audiences and income in order to make more movies. I want cinema companies to make more movies, and in fact I want them to make movies that are as outstanding, and rich, and deep, and with as high of production values as this movie has.

Similarly, people who like professional sports want their sports to be awe-inspiring. And so on.

However, what the movie illustrates is the danger of spectacle. Extreme danger. Horrible danger. And so if we are going to listen to the message of the movie, we need to listen to the message of the movie. By participating in spectacle, we are participating in all of the horrible outcomes that spectacle engenders. Some examples: professional football players and head trauma, movies that exploit local contexts, shows that numb audiences to real tragedy and humanity.

It's hard to be honest about our own complicity in the horrors of spectacle--yet if this movie has any kind of message at all, it is this message, Be aware of your complicity in spectacle.

Or perhaps the greatest danger of all, that because spectacle is so attractive, so alluring, it begins to dull our sensibilities, and so those things in this world that are truly good, true, and beautiful can sometimes appear less grand in comparison.

Take Easter for example. Easter isn't and shouldn't be spectacle. Yet there is a great temptation to make it show. Easter pageants that turn Easter into a faux shambles of the real thing.

Because the real Easter, the reality behind Easter, is both less grand than spectacle (there is no glory on a cross) and elusive (an empty tomb and a hard-to-identify resurrected Christ, recognized in shared meals and ordinary teaching).

That's all I've got for now. Perhaps more on this later, after Easter.