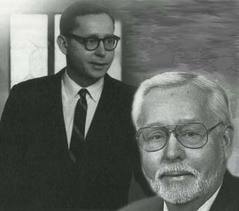

Gerhard Forde is one of the great teachers and theologians of the church, of any era. As the progenitor of “radical Lutheranism,”[1] he has influenced an entire generation of Lutheran pastors, and his dialogues both ecumenically and internationally have ensured that the unique voice of Luther and Lutheranism have been heard, resoundingly, in various contexts. There have been a variety of stages in my tutelage under this faithful preacher of the gospel, and it is important in the analysis of his preaching that I begin with this brief biographical engagement.

One distinct memory I have is of sitting up late into the evening writing a final paper for his class in systematic theology, being frustrated that what I was doing, in effect, was reconstructing the notes I took from his class and shaping them, verbatim, into a systematic theological argument. I had the impression that I would receive a higher grade if I simply parroted back what I had heard in his lectures rather than assert or construct my own theological position. I was paraphrasing so closely it felt like I was plagiarizing. I got an A, but finished the class with a bad taste in my mouth.

It was only much later, while in Slovakia serving as a missionary with my denomination, that the wisdom of Forde’s method became apparent. I found that in various settings, I was able to articulate a Fordean theological interpretation of the confessions and Scripture. I was grounded in his thought enough that I could articulate it coherently, and this coherency also set me free to move articulately beyond his thought.

In the course of my academic career, I have learned from professors with a wide variety of teaching styles. Many have taught me to think critically, and some have passed on their own views in the process. But no other professor required of his students at quite the same level a wholesale appropriation of their way of thinking. It was more like an apprenticeship, or discipling. By learning Forde’s theology, I actually learned more what I think, than if I had simply been asked, in a dialogical style, “So what is your constructive theology?”[2] Self-discovery works best in the context of the discovery of others, and (apparently counter-intuitively in the modern world) tradition-ing is more freeing than open discussion and groundless dialogue.

My short autobiographical account is important for this analysis of Forde’s theology of preaching precisely because it is indicative of how Forde preaches, and how he learned his own theology. Forde does theology as a student of Martin Luther.[3] He hopes his preaching is faithful to the radical gospel as proclaimed by Luther. “Luther’s cause, we should not forget, was the gospel of Jesus Christ, justification by faith alone without the works of the law and what happens when someone finally hears that.”[4] And what distinguishes Forde from other Lutheran theologians on this point is those last eight words, “And what happens when someone finally hears that.” Forde cherished nothing more than to find many different ways to emphasize the oral proclamation of the gospel. He believed that “theology is for proclamation.”[5]

One danger in Forde’s pedagogical approach is that some students may never move beyond simply parroting what Forde taught. This is not to say that everyone needs to learn Forde’s theology only to transcend it. But faithfulness to a tradition is not the same as parroting. In my own theological development, what I have observed is a sort of first and second naiveté at work. For a time, I simply had to quote and paraphrase it over and over again, to learn how it sounded, to practice speaking and teaching and preaching it “as is.” Then, I went through a stage where I needed to disown it and challenge it at various levels. Now, a dozen years later, I am finally at a place where I have re-engaged his theology, recognize its value, and own its permanent place in my own theological worldview and homiletical canon.

In terms of a theological worldview, I have come to the conclusion that holding a Fordeite position on Lutheran theological questions while simultaneously valuing Lutheran and ecumenical perspectives that Forde did not—such as the Finnish school and its emphasis on theosis in Luther’s thought via dialogue with the Russian Orthodox—ultimately results in a more robust theology than a theology untethered to a specific tradition. For example, I believe I read Athanasius, or N.T. Wright, or Calvin, better because I have been influenced by Forde than if I had no theological mentor with which to compare these theologians.[6] I read these theologians better because I have learned from Forde, in a way unique from all other theologians, not just what theology is, but how to be a theologian, and specifically a theologian of the cross.

In terms of homiletics, Forde is the first preacher and theologian to whom I will compare my preaching and teaching. Consciously or not, I will evaluate each sermon, maybe for the rest of my life, according to this question, “What would Forde say about that?” I stand in relation to Forde as mentor to pupil. So this analysis of the sermons of Forde needs to be understood in the context of this development. I am, for better or worse, an epigone of Forde.

Who is the God Rendered by Gerhard Forde?

Forde’s God is the preached God. The preached God justifies sinners for Jesus’ sake through the oral proclamation of the gospel. Forde’s further point is that this God needs to be preached in this way over and over, so that the deaf (us) might actually hear it. You are just for Jesus’ sake. Full stop. Any questions? Then hear it again: You are just for Jesus’ sake. Full stop. Exclamation point.

Furthermore, the God rendered by Forde is a God that comes extra nos, from without. “The Word is a word from without, from outside the self and its dreams.”[7] Preaching illustrates the extra nos nature of God well, because preaching itself is a word from without. It is not a word that comes from within, from subjective meditation[8], but is rather an objective word that comes from the lips of a preacher, travels through the air, and arrives at the ear of an actual hearer. It is less possible to confuse oral proclamation with our own internal desires and thoughts precisely because it comes to us in this manner.

This God cares how this word comes to us, right down to the grammar. For example, in Forde’s sermon on Romans 12:1-3, it is the syntax, grammar, and context of the verses that Forde locks onto. It makes all the difference in the world to Forde that Paul speaks not in the imperative, active mode (Transform your life!) but in the passive, hortatory voice (be transformed). Both are exhortations, but the difference in precisely how they are hortatory keeps the hearer and preacher focused on who is doing the transforming—namely, God. So, God is not only the preached God. God is also the preacher, the One who brings the Word (often through witnesses), in order to effect the transformation.

That God speaks and how God speaks matters. Consider the introduction to his “Justification by Faith Alone”: “For who has heard of such a thing—that one is made right with God just by stopping all activity, being still and listening? What the words say to us, really, is that for once in your life you must just shut up and listen to God, listen to the announcement: You are just before God for Jesus sake!”[9] Preaching reminds us that t is God who does something, not us, and what God does is speak—a performative utterance.[10] God speaks. Listening happens. This is the God rendered in Forde’s preaching.

God is also a “dangerous and fearsome power threatening to erupt here.”[11] God is on the loose, actually out there doing stuff in the world. This God troubles Forde. The texts this God sends for Forde to preach on “bother” him.[12] This theme and the preceding one are interrelated. Precisely because God comes from without, from out there, God is on the loose. This can mean for Forde out there in the world, in political institutions, “machines, things, and other people.”[13] But eventually, in basically every Forde sermon, Forde will move away from this hidden God, God hidden yet active in the things of this world, and he will move to the preached God, a God that still causes the world to tremble, but under a different guise. As Luther states in the Smalcald Articles, “This then is the thunderbolt by means of which God with one blow destroys both open sinners and false saints. He allows no one to justify himself.”[14] Which is to say that God is fierce even in God’s forgiveness.

Although in some ways this next statement may sound strange, the God rendered in Forde’s sermons is—wait for it—God. Forde renders God by redirecting our attention to the fact that sometimes even when we think God or speak God we are failing to speak adequately of God or on behalf of God. “Who shall presume to speak a Word from the Lord? Who can speak a Word that is from without and not just another wish-wash of pious dreams?”[15] This is a very Barthian insight—if any other theologian had as profound an influence on Gerhard Forde other than Luther, it was Barth. As Will Willimon summarizes the Barthian insight in his introduction to a collection of early sermons of Barth, “Painful realization of the difficulty of speaking about God is the first great step toward true knowledge of God.”[16] Forde identifies this paradox repeatedly in his preaching, that it is difficult to speak of God and yet the preacher has the responsibility, freedom, and necessity to speak of God. This paradox is terrifying because the preacher who realizes it realizes it precisely because God is so powerfully active in and through the word they preach. As Forde recognizes in his sermon, “Yes!”: “There is something, there is a speaking, in this benighted world in which there is at last not No, but only Yes! But that is just the terror of it. Should I, can I, just say yes?”[17]

Finally, we cannot speak of the God rendered in Forde’s preaching without focusing on Christ. Forde is very Christocentric, from beginning to end. Preaching is the preaching of Christ and his cross. As he so happily reminds hearers over and over, “As the Word has it, you are just, for Jesus’ sake!—not merely foryour sake, for Jesus’ sake.”[18] Although Forde’s preaching never gets bogged down offering complex Trinitarian formula or comparisons of various complicated Christologies, he nevertheless clearly stakes out a high Christology closely connected to, although not at all points agreeing with, Gustaf Aulen’s Christus Victor motif.[19] Forde’s sermon “Jesus Died for You” best illustrates his Christology. In it, in a powerful summary fashion, he does actually compare various Atonement theories, and especially considers substitutionary atonement and its implications. But he lays the issue out in simple language, staying close to the biblical text—at one point he even says, “All we need to do is to look carefully at what actually happened”[20]—and finally concludes that “God didn’t have to be paid to forgive, but announced forgiveness through Jesus to begin with. But that is when the trouble starts. For we would not have it… we don’t need elaborate theories or doctrines of the atonement to see why his death is for us. We lay hands on him and put him to death. And he does not stop us.”[21]Jesus dies for us precisely because we cannot receive him as he is. Forde’s high Christology will not allow us to lay the blame for Jesus’ death elsewhere than our own hands, and Jesus (through his death and subsequent resurrection) is triumphant over sin, death and the devil, all of which are involved in our rejection of Christ.

What Is the Theology Behind These Sermons?

Forde’s whole theology is epitomized in his breathtaking sermon, “Yes!” This sermon encompasses so many of his themes at once. There is, as has already been demonstrated, the living and active God who comes extra nos through the oral preaching of the Word. So there is a clear focus on God in the Word. But then there is also a focus on the preacher, who needs to deliver the sermon, the “Yes!” And finally, there is the hearer; who is, though unable to understand or accept that “Yes!” is the whole sermon, nevertheless needs to hear the yes again and again.

Within that context of the movement of the preached God through the preacher to the hearer of the sermon, Forde can say, “Exactly through and in spite of our No, God said Yes.”[22] This is Forde’s powerful proclamation of the cross of Christ drawn in miniature. No atonement theory is necessary. Just a flat out admission that we said No to God in Christ, but God in Christ said Yes anyway. As he says later, “After all, we killed him for it, but that only gave him the opportunity to say it again, Yes!”[23]

In fact, there is an entire theology of the cross backside of this sermon, and the theology implicit is connected to Forde’s lifelong reflection on what it means to be a theologian of the cross. One aspect of this theology is an emphasis on “passive righteousness.” This is best illustrated in Forde’s sermon on “Justification by Faith Alone”: “What the words say to us, really, is that for once in your life you must just shut up and listen to God, listen to the announcement: You are just before God for Jesus’ sake!”[24] The power for justification is in the words themselves that proclaim the Word, rather than in our understanding or acceptance of the words.

This is connected to a deeper theological point in Forde, a consistent understanding of God from creation itself, through the incarnation, all the way to salvation. It is the same God who says “Let there be light” through the Son of God, the Word, who later says “You are forgiven.” Forde preaches, “So God speaks to show his righteousness. The words are intended to do what God’s Word always does, to create out of nothing, to call something new into being, to start a reformation. God, that is, has decided just to start over from scratch. So listen up!”[25] This takes passive righteousness to whole a new level, and parallels it with creation ex nihilo. The justifying Word is the creating word and vice versa. God speaks and ipso facto creation. God speaks and ipso facto justification.

This is obviously a homiletical theology, with a strong soteriology focused on justification. Concomitantly, Forde’s theology has very little ecclesiology. This is a strength, because it keeps preaching focused on God and the power of the Word. Indeed, one searches long and hard for any kind of instructions or directives to the hearers on how they should live a common life together.

However, as we will see in the next section, this heavy focus on the preached word does have a certain docetic tendency. Forde does not appear to think of the church as a real body, at least not in these sermons. Even though Forde emphasized a theology of the cross, defended classic Lutheran doctrines like the real presence of Christ in the supper, and can even be said to have had a very deep sacramental theology, nevertheless there is a tendency to docetism inasmuch as Forde’s theology of preaching remains always in the event of preaching itself with little that connects with an on-the-ground ecclesiology or sense of the life together of a Christian community gathered around the preached Word.

What Are the Theological Weaknesses Revealed in These Sermons of Forde?

Forde readily admits some of his own weaknesses, possibly because so many hearers of his preaching and teaching have brought them as complaint directly to his door. The primary weakness can be illustrated by examining how he concludes his sermon “Justification by Faith Alone.” He proclaims, “There is nothing for me to do but just say it: You are just for Jesus’ sake. And there is nothing for you to do but just listen. Believe it, it is for you! It will really reform your life!”[26] There is nothing for me to do? Really? Can’t we say anything, then, about what this reformed life looks like?

Forde is adamant that preaching is not about moral instruction, paraenesis, growth, faith practices, or a description of what this new life accomplished through the word might look like. Most of it would amount to a “third” use of the law, an understanding of the law Forde opposed and thought was actually just a return to the first under a new guise.[27] One sermon in particular that I have chosen for this analysis illustrates this common theme in Forde’s work. He begins a sermon on Romans 12:1-3 with these words:

“I am not at all sure that I like that text. That may come as no surprise to many of you, perhaps especially those of you who keep nipping at my heels [!] to get me to say something about the Christian life, change, progress, and the like. But what bothers me about the text is not, I expect, what you might think. If it were simply a matter of change, or of making some sort of progress toward what we might call perfection or whatever, I reckon I could manage that as well as the next person. Like Paul, I don’t want to boast, but if you want to argue on that human level I don’t know that I am doing so badly! I come from three generations of pastors, have one wife, pay my dues and taxes, try to take care of my kids, go to church, work hard, keep publishing, stay out of debt, remain under the law—blameless, one could say (sort of, anyway!)”[28]

Forde simply does not think that preaching is primarily about moral exhortation of any kind. Preaching is, as we have already indicated, about justifying sinners for Jesus’ sake. What preaching accomplishes in terms of ethics and Christian community is something other than change or progress. Instead, it is a certain kind of transformation, a “lucidity about who we are and what we are up to.”[29] Luther, in his Heidelberg Disputation, said that a theologian of the cross “calls a thing what it is.”[30] So the transformation is not something we are told to do, but again, passively, something done to us, “with all the illusion gone in unveiled faces beholding the glory of the Lord—that’s what does it, the shock of that grace—we are being changed from one degree of glory to another. Let us believe that.”[31] As he notes earlier in the sermon, it is the syntax and grammar that matters in Paul’s quote in Romans. We are not called to “transform our life” but rather to “be transformed by the renewal of our minds.” Forde is, as always, focused on what the words do, the grammar of a thing, because the words matter and really do something, and it is the Word that has agency rather than us.

Forde makes his own weakness a slippery eel by admitting to it before we can critique it and then baptizing it as strength rather than weakness. It is a little difficult to know precisely how to deal with this. To begin with, we may note that self-awareness of a weakness does not abrogate it. Just because I openly admit that I pick my nose in public doesn’t mean my wife has an invalid complaint when she asks me to stop and put my fingers in more sanitary locations—just so with the complaint against Forde that his preaching lacks guidance on “the Christian life, change, progress, and the like.”[32] This is precisely the Achilles heal in both his preaching and his theology, and we need to stay here and think clearly in order to learn how to preach with theological rigor and profundity with Forde while avoiding this pitfall.

Forde refuses to preach about the Christian life, change, and progress for, as far as I can tell, three reasons. The first reason is anthropological, and is the most damning, for it virtually silences anyone who would even question Forde’s thinking on the matter. The second reason, this one harmatological, offers a view of humanity that does not include things like progress, growth in virtue, holiness, and the like. This second reason, less accusative in nature, is easier to engage. The third reason concerns imputed or passive righteousness, a doctrine that circles back to reason one, for it is a concept only the New Adam can understand by faith.

Reason #1: Consider Luther’s 25th thesis in the Heidelberg Disputation. He writes, “He is not righteous who works much, but he who, without work, believes much in Christ.”[33] Forde comments on this thesis: “We have a hard time getting over the offense [of this thesis], and thus there is no letup, even here. The thesis is really nothing other than a statement of justification by faith alone without the deeds of the law… That doctrine is always a polemical doctrine and a permanent offense to the Old Adam.”[34]From this Forde draws the conclusion that theology for proclamation does not include instruction in any kind of works, but is instead to be the iteration of justification by faith alone without the deeds of the law. Preaching can never move on or forward or past this point, because moving on or forward is an illusion that is actually a return to the thinking of the Old Adam rather than the freedom created by the preaching of justification.

So Forde does have a description of the Christian life, of sorts, but it is a returning again and again to that new point where faith happens. His conclusion to the paragraph cited above is worth quoting in full: “Only those who believe much in Christ are righteous before God, period. It always seems incredible to us, but getting used to that fact is what it means to die and be raised to newness of life in Christ, to be born anew. Only then will works that can be called ‘good’ begin to be done. Good works, works done for the neighbor without calculation or claim, can begin when the Old Adam is put to death and the new appears.”[35] Good works done with an eye towards what they do before God are a project of the Old Adam, are a form of works righteousness, and only works done for the neighbor without calculation, that is, almost spontaneously arising out of the new life in Christ that comes through faith, are truly good works.[36] This perspective, applied to the task of preaching, implies that anyone who questions whether good works and progress in the Christian life can be the topic of preaching, are slipping back into the thinking of the Old Adam. Instead, just preach justification again. Good works naturally proceed from righteousness by faith in Christ. Said otherwise, sanctification is simply the art of getting used to justification.[37]

Reason #2: People don’t actually grow or change. Progress is a myth, because of sin. So for Forde, since people can’t really get better or progress per se, the only thing that really does something new in their life is the preaching of the gospel. It’s not our own spiritual or moral exercises that do something, but Christ in the proclaimed word. Forde splits the person in two, between the Old Adam and the New Adam. The Old Adam can live a more or less moral law, and can strive to uphold the law. But if the Old Adam confuses this moral striving with the process of sanctification (which, we remember, is actually simply getting used to justification), then they are stuck in the oldness of the Old Adam and are in the process of dying, not growing. The New Adam has no illusions about growth or progress precisely because it is no longer they that live, but Christ who lives in them. Their growth or progress in the Christian life, inasmuch as it is such a thing, is the growth of Christ in them, not their own work. They are getting used to being justified.

Reason #3: Forde is concerned that if we preach the Christian life, change, or progress, we may be inadvertently encouraging people to believe in salvation by works of the law rather than by faith alone. He is rightly concerned, together with other theologians like Will Willimon, that many preachers, “unable to preach Christ and him crucified… preach humanity and it improved.”[38] This third reason is Forde’s red herring, because it fails to make a distinction between preaching the law as salvific, and preaching as instruction for communities on how to live life together. Even if we concede Forde’s point, that preaching the virtues, Christian life, etc., is simply a concession to the demands of the Old Adam, it is not at all clear that this is not one appropriate function of biblical preaching.

Let us take Forde at his word. In his sermon “We Are Being Transformed,” Forde writes, “If it were simply a matter of change, or of making some sort of progress toward what we might call perfection or whatever, I reckon I could manage that as well as the next person. Like Paul, I don’t want to boast, but if you want to argue on that human level I don’t know that I am doing so badly! I come from three generations of pastors, have one wife, pay my dues and taxes, try to take care of my kids, go to church, work hard, keep publishing, stay out of debt, remain under the law—blameless, one could say (sort of, anyway!).”[39] This is all fine, and helps Forde move towards his point, that “we are being transformed” rather than actively transforming ourselves. However, one can legitimately ask: How did Forde come up with this particular list of items that constitute blamelessness or perfection? What led him to believe that having one wife, paying taxes, working, etc. all constitute grounds for boasting? Isn’t it of interest, at some point in the work of preaching, to ponder these things? One searches Forde’s sermons for such exploration and finds little of it. It is a lacunae in his preaching, and seems likely to lead, over time, to the lack of formation of the church according to the full biblical witness.

What Are the Theological Strengths of Forde’s Way of Preaching?

Is it possible for a theological strength to be pithiness? If so, this may be Forde’s greatest strength as a preacher.[40] In terms of word count, his sermons are incredibly short, often less than two pages in print. This brevity has to do with the pacing of his oral presentation. He speaks slowly, resolutely, carefully. I was present in the Luther Seminary chapel when Forde preached his sermon published as “A Word from Without.” It may be the most memorable sermon I have ever heard. His pace was slow and deliberate. He had a quiet, Scandinavian lilt to his speech. The room hung on every word. He began the sermon simply quoting Jeremiah, “Is not my word like fire, says the Lord, and like a hammer which breaks the rock in pieces?” (23:29) The power of the sermon was not illustrated through loud voicing or drama. Almost the opposite prevailed. Nevertheless, by the time he got to his last paragraph (there are only seven paragraphs in the whole sermon), I was convinced that the Word of God was like a hammer, and I should duck. Then he said:

“So I must say it one more time since it is a matter of your eternal destiny, and it is so much fun to say: You are just for Jesus’ sake, says the Lord. Now, there, is not my Word like fire, says the Lord, and like a hammer that breaks a rock in pieces?”[41]

This sermon exhibits strengths on a number of levels. First, it is strong in the direct sense of proclaiming the strength of the Word of God, literally. God’s Word is like a fire or a hammer. Second, the sermon is strong because it illustrates the theological truth of Jeremiah in the very way that the sermon is delivered. A hammer is not strong if it flails around and misses its mark. But struck in the right place, it can indeed break a rock in pieces. This is how Forde’s precision is a theological strength. It takes aim exactly at the bed line or grain, and strikes there. No chopping around the edges or ineffectual strikes. Aim straight and true for the place where the Word will strike terse as titanium, then strike, hard.

Third, it is theologically strong because it takes words that were on the lips of Jeremiah (a preacher) and places them on the lips of a contemporary preacher (Forde) in a way that makes the text come alive both as the preaching of Jeremiah and as the preaching of Forde—and what is more, the very preaching of the Lord. Preaching is by nature multivalent, because it is a word (sermon) coming from the Word (Scripture) in the Word (Christ). As Bullinger says in the Second Helvetic Confession: “The preaching of the Word of God is the Word of God.”[42] Preaching is beautiful and powerful when it exercises this multi-valence. From a doctrinal perspective, the preached Word of God is the Word of God even when it is not directly illustrating the point, but when a text can speak on so many different levels, including the historical voice of the prophet, the living word of the preacher, and the living and active Word of God, something happens, something new comes into being, and it happens as a kind of literary event.

Will Willimon in his Conversations with Barth on Preaching notes that Barth also elevated preaching to equal status and similar function of Scripture in a way comparable to Bullinger. He notes that Barth’s view of preaching is a scandal because it makes the “outrageous claim that the words of Christian preachers are identified with God’s own Word.”[43] This is a captivating and striking concept, influential in Willimon’s own theology of preaching, and illustrated in another great theologian contemporary with Barth. Dietrich Bonhoeffer offers an arresting image of how the words of Christian preachers are God’s own words.

The proclaimed word is the incarnate Christ himself. As little as the incarnation is the outward shape of God, just so little does the proclaimed word present the outward form of a reality; rather, it is the thing itself. The preached Christ is both the Historical One and the Present One... Therefore the proclaimed word is not a medium of expression for something else, something which lies behind it, but rather it is the Christ himself walking through his congregation as the Word.[44]

A strength of Forde’s preaching is that it kept company with theologians like this, who trusted that the Word of God truly is present in, with, and under the words of the preacher.

However, Forde also keeps company with these theologians by maintaining the paradox of God hidden and revealed. In preaching, “God is revealed, but revealed in a way that manages both to hide and reveal.”[45] [possibilities here for expanding the paradox of hidden and revealed include the Barthian paradox that we cannot speak of God but we must speak of God; also Barth’s emphasis on repetition (Willimon on Barth page 181); the poverty of preaching is its strength (page 241)

Forde’s historically attentive homiletical theology comes alive in the interplay between theology and preaching. In fact, Forde is an exemplar of the dynamic mutual interplay between theology and proclamation. This interplay comes alive especially in his theological assertion that preaching doessomething, and is illustrated in the structure of his sermons, most of which function as truly “performative utterances.”[46] In his classic book Theology is for Proclamation, Fordes writes, “A sermon does indeed include explaining, exegeting, and informing, but ultimately it must get around to and aim at doing, an actual pronouncing, declaring, giving of the gift. In proclaiming the Word, our goal is absolution, the doing of the deed that ends the old and begins the new.”[47] Forde “gets around to” the doing much more quickly than the average preacher, possibly because he hears so many sermons that remain mired in the explaining, exegeting, and informing, and never get to the doing, and so his sermons need to illustrate the doing more quickly and dramatically for the sake of balance.

The literature on preaching often reflects on the performative aspect of preaching. James Kay titles it “promissory narration,” preaching that tells the narrative of Christ (though not necessarily all of it) as a “’performative utterance’ by a ‘self-involving’ agent” that enacts the promise.[48] Thomas G. Long, in a similar fashion, comes to the conclusion that preaching may be understood as “bearing witness,” bringing a word back of what one has seen or heard, usually by the preacher who is “the one whom the congregations sends on their behalf, week after week, to the Scripture. Forde’s preaching is performative in each of his sermons, although how the sermon does something differs slightly from sermon to sermon. In “Jesus Died for You,” the doing comes through repetition of the phrase “Jesus died for you” as the first and last sentences of the sermon, and often in between. In “Yes!” it is through the rhetorically powerful question and answer session he sets up as the conclusion of the sermon. In “Justification by Faith Alone,” the word is performed by rather direct, even rude speech, telling the hearers to just “shut up and listen to God,” who is saying, “You are just for Jesus’ sake!” In “We are Being Transformed,” the performance occurs more through the inductive method, bringing the hearers along on a discovery Forde made while exegeting the text, that it says “we are being transformed” rather than “transform your life.” Finally, in “A Word from Without,” the word is done to us precisely in the iteration that the word is done to us, it comes from without, from outside us, and it can do something precisely because it is not our word but a word from without.

[1] “We should realize first of all that what is at stake on the current scene is certainly not Lutheranism as such. Lutheranism has no particular claim or right to existence. Rather, what is at stake is the radical gospel, radical grace, the eschatological nature of the gospel of Jesus Christ crucified and risen as put in its most uncompromising and unconditional form by St. Paul. What is at stake is a mode of doing theology and a practice in church and society derived from that radical statement of the gospel. ... I do want to pursue the proposition that Lutheranism especially in America might find its identity not by com- promising with American religion but by becoming more radical about the gospel it has received. That is to say, Lutherans should become radicals, preachers of a gospel so radical that it puts the old to death and calls forth the new, and practitioners of the life that entails ‘‘for the time being.”http://www.lutheranquarterly.com/Articles/2006/Special-Issue-20-Years/02-lq_forde.pdf, accessed April 4, 2010.

[2] It may be that we only learn to think by first learning what others think. Which illustrates the error of parenting that says, “We’ll let our kids grow up to believe what they want to believe.” They never will.

[3] And to almost a similar degree, Karl Barth.

[4] Gerhard Forde, A More Radical Gospel: Essays on Eschatology, Authority, Atonement, and Ecumenism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 207.

[6] For further reflection on this point, see my essay “Why I am a confessional Lutheran” athttp://www.lutheranforum.org/extras/why-im-a-confessional-lutheran/, accessed April 6, 2010.

[7] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 92.

[9] Ibid. 86.

[10] J.L. Austin. How to Do Things with Words (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962) is incredibly influential in Forde’s theology.

[11] Gerhard Forde, The Preached God: Proclamation in Word and Sacrament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 319.

[12] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 112.

[13] Ibid. 92.

[14] Ibid. 92.

[15] Ibid. 92.

[16] Willimon, William. The Early Preaching of Karl Barth: 14 Sermons with Commentary (Westminster John Knox, 2010), xii.

[17] Gerhard Forde, The Preached God: Proclamation in Word and Sacrament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 320.

[18] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 87.

[19] Aulen, Gustaf. Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of Atonement. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003.

[21] Ibid. 222.

[22] Ibid. 320.

[23] Ibid. 321.

[24] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 86.

[25] Ibid. 87.

[26] Ibid. 90.

[28] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 112.

[29] Ibid. 115.

[30] http://www.bookofconcord.org/heidelberg.php#21, accessed April 8, 2010.

[31] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 115.

[32] Ibid. 112.

[33] http://www.bookofconcord.org/heidelberg.php#25, accessed April 8, 2010.

[34] Gerhard Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross: Reflections on Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation, 1518 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 104.

[35] Ibid. 104.

[36] “Faith cannot help doing good works constantly. It doesn't stop to ask if good works ought to be done, but before anyone asks, it already has done them and continues to do them without ceasing,” from Luther’s Introduction to to St. Paul’s Letter to the Romanshttp://www.iclnet.org/pub/resources/text/wittenberg/luther/luther-faith.txt, accessed April 8, 2010.

[37] Donald Alexander. Christian Spirituality: Five Views of Sanctification (IVP Academic, 1988), 13.

[38] William H. Willimon. Peculiar Speech: Preaching to the Baptized (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 9.

[39] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 112.

[40] Compare this to “von Balthasar’s seminal observation that Barth ‘did not write well because he had a gift for style. He wrote well because he bore witness to a reality that epitomizes style, since it comes from the hand of God.” William H. Willimon. Conversations With Barth on Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006), 91.

[41] Gerhard Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 93.

[43] William H. Willimon. Conversations With Barth on Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006), 231.

[44] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Worldly Preaching: Lectures on Homiletics (Clyde E. Fant, ed. and trans.; New York: Thomas Nelson, 1975) 126.

[45] Willimon, William H. Conversations With Barth on Preaching. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006, 231.

[46] Note J.L. Austin’s influence on Forde’s theology here.

Don't teach options. Be an option.

ReplyDeleteNo doubt I learned a whole lot from Forde in my years at Luther too.

ReplyDeleteMaybe the greatest gift is to know God is other than me and my imagination. And He comes for me in the Word. The idea that the Word is other than me is a challenge headed straight for the old Adam.

We want to imagine ourselves at one with God--but what we find is that God comes for us. More than that I need him to come for me; because without him coming to save I have no hope.

I took every class Forde offered in 77-81. While I am disappointed by the turn he took against the ELCA (part of which was the rejection of the ELCA of the role of seminaries as teaching institutions for the whole church, an ALC position that served that tradition well), his preaching and his teaching still warm my heart in ways that only David Lose does today.

ReplyDelete